As you break into the world of UX design, you’re likely to encounter the term “usability” on a regular basis. It’s a fundamental concept in UX that’s simple enough—but what is it, really, and how do you make it happen in your designs?

Usability is a simple concept, yet so powerful that it can derail even the most amazing product concepts and sleekest of designs if it’s not implemented well. Put very simply, usability is the ease with which a person can accomplish a given task with your product. And whether you’re designing a login screen, a search experience, or anything else you can imagine, usability is essential!

In this guide, we’ll define usability, show the differences between usability and other important concepts (UX and accessibility), and talk about how you can make your designs as great and as usable as your users need want them to be!

Here’s what we’ll cover:

- What is usability?

- What makes a product usable?

- Usability vs. UX

- Usability vs. accessibility

- How to make your designs usable

- A final word

- Frequently asked questions (FAQ) about usability

1. What is usability?

As we’ve said, usability is how easily a person can accomplish a given task with your product; it is the result of intentional, research-based, and user-tested design decisions made with one goal in mind: to make it as easy as possible for users to do what they need to do with the product.

Usability is a key element in the design hierarchy of needs and in Peter Morville’s UX honeycomb—both of which are models that help us break down what can become a complex tangle of research data, tests, prototypes, and more. These models visualize the essential components that well-designed products take into active consideration.

Usability is rarely—if ever—accidental. If you leave usability up to chance, you’re likely to end up with a product that’s great in theory, perhaps even visually striking, but ultimately inefficient or frustrating to use. Rather, usability is the result of choices that designers make based on solid research and testing.

If you have a mobile phone that you enjoy using, chances are that its designers did a good job researching and testing to fine-tune the usability of the device. Of course, you might still put up with a phone that’s got poor usability, but in that case, there are likely other elements (elsewhere in hierarchy or in the user experience as a whole) that compensate for the usability problems—at least for a time.

(Note that most UX design principles contribute in some way to a product’s overall usability.)

2. What makes a product usable?

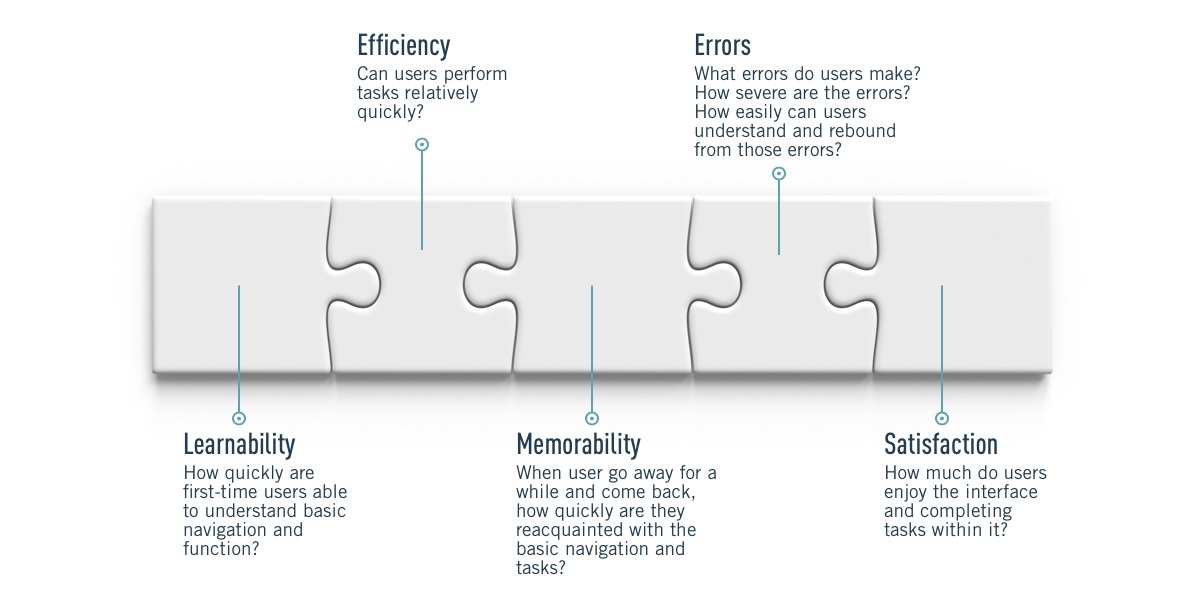

A product’s usability is based on five core qualities that you can test for (we’ll cover testing briefly in section 5 of this guide). Write these down, commit them to memory, tattoo them on your arm (or…don’t)—they make a huge difference in the overall quality and success of your product. They are learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction.

- Learnability. How quickly are first-time users able to understand basic navigation and functions?

- Efficiency. Can users perform tasks relatively quickly?

- Memorability. When users go away for a while and come back, how quickly can they reacquaint themselves with the basic navigation and functions?

- Errors. What errors do users make? How severe are the errors? How easily can users understand and rebound from those errors?

- Satisfaction. How much do users enjoy the interface and completing tasks within it? (Both as they are using the product and how they report satisfaction afterwards.)

3. How does usability fit into UX?

Wait—did you say “elsewhere in the user experience”? I did. Usability and user experience (UX) are not the same thing. Usability is a critical part of good UX, but these are two different concepts that guide us to consider different aspects of the design process.

Usability refers to how easy a product is to use—how easily you can accomplish a given task with the product. UX refers to the overall experience users have with the product, from beginning to end. Let’s go with an example to show the difference. Storytime!

You’re looking to buy a new e-reader (Kindle, Nook, etc.), so you go to a website you’ve heard had a good selection and you easily navigate to the right section of the site. You find the selection of e-readers you’re looking for, and as you browse product pages, it’s easy to understand the specifics for each option—hardware, price, accessories, warranties, etc.

You find the e-reader that best suits your needs, and you buy it. The check-out process is simple and quick, and you’re done!

Or are you? They don’t sent you many notifications on the status of the shipment, but your purchase is delivered two weeks later. You’re excited to get the device all set up and populated with your favorite reads, so you tear open the box—only to find that the device is damaged. You can’t even get it to turn on, and you’ve tried everything.

You get back online to see about returning or exchanging the device. You click around on the site and wonder where their contact information is listed. It takes a little digging around, but you finally locate a toll-free number for customer service. It’s a little frustrating after all that to call and be put immediately on hold with no indication of how the wait might be.

But you wait. And you wait.

The hold music is terrible and so you’re a little grumpy when the representative is finally on the line. Regardless of the situation and your feelings, you do your best to stay friendly and calm on the call. The representative, however, doesn’t really seem to care about the problem and it’s like pulling teeth to get them to give you clear instructions.

You finally succeed in getting a somewhat clear idea of the process for exchanging the device, but it involves them sending something to you to send the device back with and you encounter problems with getting the return package put together.

You finally just ship it off to the company, but they’re not very communicative and even when you call to check the status, it takes forever and a day to get any information. A month later, you receive a new, undamaged e-reader in the mail.

Whew! Was that as stressful for you to read as it was for me to write? Here’s why we bothered with the example at all. Usability came in to play as you shopped on the website, found the e-reader you wanted, and ordered it. It was straightforward, easy, and quick.

The site’s usability was somewhat less stellar when it came to finding a way to contact customer service. You had to do a little digging around. Maybe that was intentional on their part; maybe not. But at a relatively anxious touchpoint in your customer journey, you weren’t finding what you needed when you needed it.

And the rest of that narrative is UX—your experience with the company and their products from beginning to end. The long wait, the bad music, how you were left in the dark regarding the wait time, the attitude of the person you spoke with, and the lack of clarity on how to accomplish a simple task—exchanging an item. This is all UX.

If we were going to rate this site’s usability, it might get 3-4 stars out of 5; it’s UX, however? It might depend on when in the long and mostly painful journey you decided to give a rating.

4. What’s the relationship between usability and accessibility?

Now that you see the difference between usability and UX, let’s break down the differences between usability and another important consideration: accessibility.

Usability and accessibility are related but separate considerations. Both are important considerations if you want to design inclusively.

Just as good UX includes usability, good usability includes accessibility. Accessibility is usability applied thoroughly and in consideration of users who may not have the same physical or cognitive capabilities as your “average” user.

Accessibility is all about making products equally usable and enjoyable to people regardless of their abilities or what assistive devices they use to access the product. Spencer Ivy illustrates the relationship between usability and accessibility using the metaphor of a really great beachfront property. There’s this really great beach area with restaurants and music; all your friends are there, and it promises to be a really good time. The only catch is that there is no way for you to access the beach. And what good is an awesome beach party without a way to get to it? You’re left trying to just be happy for the friends you have who were able to go.

There’s no way for you to know how many users—or potential users—are affected by any permanent, temporary, or situational limitations (terms borrowed from the inclusive design toolkit) in their ability to access your product. The reality is that if you’re not taking accessibility into account, you’re actually creating a product that likely isn’t usable for a significant number of your users at any given time.

For example, one person has experienced permanent hearing loss; another is dealing with temporary hearing loss due to an accident or medical procedure; and another can’t hear over their neighbor’s blaring music for a few hours on a Saturday night. If your product is designed only for people who can hear everything, all the time, it’s not accessible to these users or others like them.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines from W3C provide a good standard for ensuring that digital products are fully accessible and do not exclude users on the basis of their physical or cognitive abilities.

For something a little more engaging and with an even broader scope, Microsoft Design’s inclusive design process (based on Kat Holmes’ toolkit, linked earlier) goes beyond mere accessibility, and is a fantastic resource if you want to learn about how to design in ways that do not exclude any user on the basis of ability, gender identity, background, or experience.

To learn more on this topic, check out these guides:

- Universal design vs. inclusive design (what’s the difference?)

- 7 Universal design principles to follow

5. How to make your designs usable

The most important thing to remember when you’re aiming for great usability for your product: you can’t add “a little usability” in at the end—or at any one point in the design process. It will always be more than a little sprinkle of usability. It takes attention and effort throughout the design process.

And what will those efforts look like? Three words: research and testing.

If you grasp at design solutions without researching and understanding the real problems are, you’ll find your efforts about as effective as taking unknown medication for a head cold. Might work, probably won’t, and likely to cause some weird side effects.

Similarly, if you’ve conducted extensive user research and implemented what seem to be really awesome design solutions, but you never conduct usability testing on those solutions to see if they’re actually making the product more usable, you won’t know how to improve on those solutions until new problems have sprouted. Research and testing, folks—don’t skimp on these two elements!

As you go about research and testing, here are some questions to guide your efforts:

- Who are the actual users of this product and what brings them there?

- Who are the potential users and what’s keeping them from using the product?

- What are the relevant contextual factors for these users? What environmental, situational, temporary, or permanent considerations might affect how usable the product will be?

- Why do users want this product/experience? What do they want to accomplish with it? What are the Jobs-To-Be-Done?

- What gets in the way as users try to accomplish what they want to do with the product?

- How might you eliminate obstacles to create more efficient, effective, and enjoyable user experiences?

Typical UX tools and processes, when implemented well, naturally take usability into account—and this is true throughout the UX design process.

In the beginning, your focus is on researching user needs and pain points. It’s your job to really listen and observe what your actual users (or prospective users) want, need, and encounter when using your product. You do this by conducting user experience research and interpreting the resulting data into:

- Affinity diagrams

- Customer journey maps

- User personas or persona spectrums

- Any other deliverable that helps visualize the needs that your solutions should address

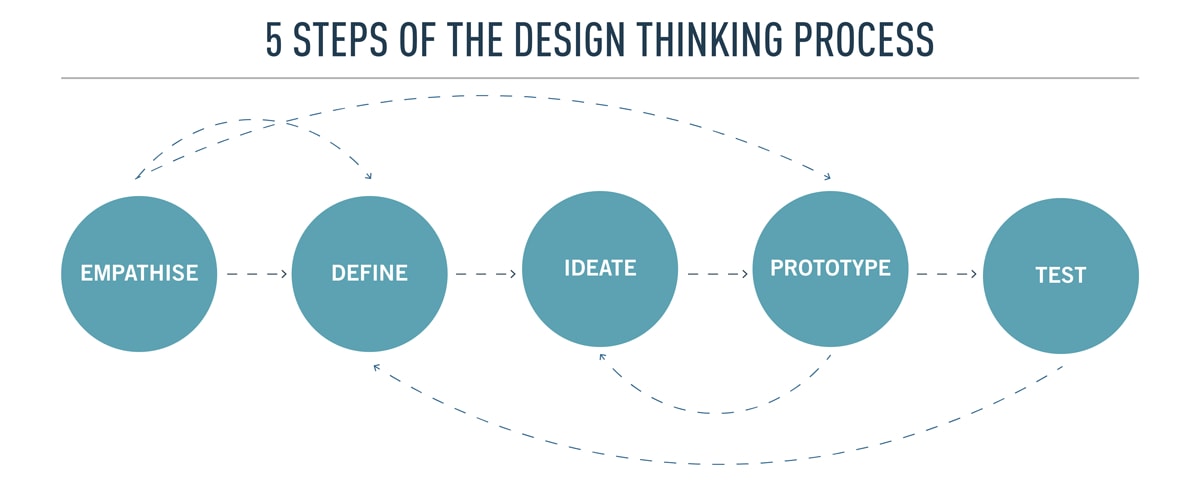

You should take usability into account with every single one of these deliverables, and keep it at the forefront of your inquiry throughout Empathize and Define stages.

During the Prototype and Test stages, it’s critical to constantly reference the deliverables you created in the research phase. Keep usability at the forefront as you’re testing—even (or especially) when you’re still working with prototypes and wireframes.

6. A final word

Usability is a key component of a good product or experience. You can have the most flashy designs and snazzy UX, but with poor usability, your users will encounter problems that could (and probably will) eventually drive them to use other products.

Let’s return for a moment to our example of buying an e-reader. What if the narrative were flipped around? So the overall UX (how you heard about the company, your communication with the company, the process of returning/exchanging the damaged item) was simply spectacular and the usability (your ability to navigate the site itself and complete your task—from research to purchase) was just awful. Would you return to that company/site? Would you even complete that first order? Probably not. At least not without some pretty serious doubts.

Neglect the usability of your designs and you’re likely to wind up with a product that people avoid using—which is far from ideal. So don’t be afraid to ask the tough questions and make sure that your product is actually usable by the people who are using it.

If you want to learn more about UX design how to make better experiences for all users, check out these articles:

- UX vs. CX: What’s the Difference?

- What is skeuomorphism in UX design?

- The importance of simplicity in UX design

- 5 Brilliant Examples of UX design in the real world

7. Frequently asked questions (FAQ) about usability

1. How do you define usability?

Usability refers to the ease of use and overall user experience of a product, system, or website. It focuses on how effectively users can interact with the interface and accomplish their tasks with efficiency, satisfaction, and minimal frustration.

2. What is an example of usability?

An example of usability is a mobile banking application that has a clean and intuitive user interface, allowing users to easily navigate through various features such as checking account balances, transferring funds, and paying bills. The application provides clear instructions, logical workflows, and responsive design, making it effortless for users to perform banking tasks on their mobile devices.

3. What is usability in terms of UX?

Usability, in terms of user experience (UX), refers to the extent to which a product or system can be used by users to achieve their goals effectively, efficiently, and with satisfaction. It encompasses various aspects such as ease of learning, ease of use, error prevention, and user satisfaction, all contributing to a positive overall user experience.

4. What are the four factors of usability?

The four factors of usability, often referred to as the “4 E’s,” are as follows:

Effectiveness: This factor focuses on how well users can accomplish their goals and tasks when using a product or system. It assesses the accuracy and completeness of user interactions and the ability to achieve desired outcomes.

Efficiency: Efficiency relates to the resources required, such as time and effort, to accomplish tasks successfully. It involves minimizing user effort, reducing unnecessary steps, and optimizing workflows to streamline the user experience.

Learnability: Learnability refers to how easily users can understand and learn to use a product or system. It assesses the initial user experience, intuitiveness, and the availability of appropriate guidance and documentation.

Satisfaction: Satisfaction gauges the overall user satisfaction and enjoyment derived from using a product or system. It encompasses factors such as aesthetics, ease of use, perceived usefulness, and emotional response, ultimately determining the user’s overall impression and likelihood of continued usage.